Team Dragonair’s project manager Mariah Cain gained first-hand experience in turning creative sparks into tangible projects at a young age, growing up in her grandfather’s machine shop. Eventually, she moved out of her small town and began working at a 3D imaging company in Arizona. There, she became interested in Hydroflight, a competitive sport in which athletes maneuver on water-powered hoverboards connected to jet-skis. It was through their mutual interest in Hydroflight that Cain met her now-teammate Jeff Elkins, who was working to marry the technology behind Hydroflight devices and drones to develop a new class of personal flyers.

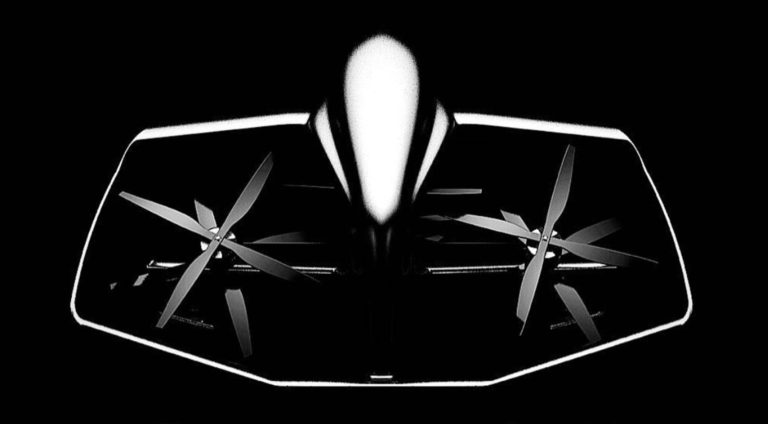

Far more than just an enthusiast, Elkins, who has been called a “mad scientist” by his peers, is a drone pilot with extensive engineering experience, having designed everything from prosthetic limbs to architectural renderings. His expertise, along with Cain’s own growing interest in Hydroflight and personal aviation, drove Cain to move down to Florida and get serious about what she once considered just a hobby. There, she started working closely with Elkins and his colleague Ray Brandes on Elkins’ most ambitious project to date—the Airboard, a flying device that gets its power from eight motors and its maneuverability from the human body.

Over time, a true team took shape, complete with a clear vision, engineering prowess and perseverance. But making a flying device is a monumental challenge, not to mention the work that goes into securing funding, gaining industry recognition, and attracting public interest. As project manager, Cain knew she had to find ways to make these critical elements come together—that’s when she heard about the GoFly Prize.

A Team of Pilots and Engineers

Though the GoFly Prize challenge was issued in September 2017, Cain and her colleagues only learned about the opportunity in April 2018. Having missed the Phase I submissions deadline, Cain, Elkins, and Brandes joined the competition during Phase II, incorporating as team Dragonair and completing their entry just in the nick of time.

Their device—now called the Airboard 2.0—has undergone many iterations even before Dragonair joined GoFly, but the team had to make a number of new key changes to be considered for Phase II. They needed to make their prototype smaller, boost flight time without overloading the device with heavy batteries, and obtain new test parts for their improved model.

Through it all, Cain has played a major role in experimentation, flying the Airboard using her body movements to control it—just take a look at her impressive flight on YouTube. “Many people ask me if it’s scary to fly, but because of all the safety stabilization, it feels natural. It’s exciting to be one of the first women involved in this style of flight. I’m grateful that I get to be a part of such a unique field at such an incredible time in history,” Cain says.

Creating the feeling of freely flying through the air, uninhibited by a massive device, was a big factor in Dragonair’s design process. “The Airboard enables you to interact with the natural world around you. It’s very empowering compared to other technologies that take away from the human connection with nature. The Airboard’s design allows the pilot to feel like they are one with the device, informing its motion by shifting their weight it in a standing position. Once people get a taste of what it’s like to fly these things, they won’t be able to get enough,” Cain says.

Don’t let the team’s focus on pure human flight fool you, though—for Dragonair, safety is a major priority. Already, the device has a mechanism in place where it can continue to fly even if up to four of its eight motors give out. In total, there are three tiers of safety conditions in place to ensure that flights are safe. For example, there will be two separate parachute systems installed (one for the pilot and one for the device).

Making the Inevitable Real

As futuristic as the Airboard may seem, it’s becoming real faster than Dragonair had imagined. Cain and Elkins say that the progression from unmanned drone to personal flyer is inevitable, especially once people can envision all the possible applications of these devices. So how does team Dragonair expect the Airboard to be used? Recreation, of course, will be a big draw. But Cain has loftier ambitions as well: “We need to get more girls on these devices to show the world what women can do,” she says.

She also believes that there’s a great deal of potential when it comes to search and rescue operations.“I recently lost a good friend to a riptide,” she says. “When something like that happens, all these boats and helicopters are dispatched but it’s so hard to find someone when you’re on such an unwieldy vehicle. A smaller device with a spectral camera can make it easier to find people and save lives.”

Personal flyers can even drive change in the agricultural space, where the eradication of harmful plants is currently not done in the most environmentally sound way. Today, aircraft with limited targeting capabilities spray harsh chemicals on massive areas of wildlife, killing not only certain flora but also their surrounding ecosystems. A heavy-lifting drone—manned or unmanned—can execute that task more sustainably simply because it can get lower to the ground and aim more precisely.

“There’s really no limit to how these devices can add efficiency to different industries,” Cain says. “We can’t wait to finally complete the Airboard that we’ve dreamt about for so long and show the world its capabilities.”