Editor’s Note: Over the next year, we will be hosting a series of GoFly Master Lectures where industry experts share advice, insights, and answer questions from GoFly Teams.

For the latest in our series of “Master Lectures,” we welcomed Irene Gregory, NASA Senior Technologist (ST) for Advanced Control Theory and Applications. Her current interests are in the areas of robust autonomous systems, self-aware vehicle intelligent contingency management, acoustically-aware vehicles, and resilient control for advanced, unconventional configurations with particular focus on Urban Air Mobility. Previously, Dr. Gregory’s research spanned all flight regimes from low subsonic to hypersonic speeds, and included advanced control for aircraft and launch vehicles, aeroelasticity, fluidic control effectors, and autonomous vehicles. Her research has been documented in over 100 technical publications in peer-reviewed journals and conferences, invited lectures and presentations.

Dr. Gregory earned a Bachelor’s Degree in Aeronautics and Astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a Doctorate in Control and Dynamic Systems from California Institute of Technology. She is an Associate Fellow of the AIAA, a member of IEEE and IFAC, serves on IEEE Control Systems Society Aerospace Control Technical Committee and on IFAC Aerospace Control Technical Committee. She is an emeritus member of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation and Control Technical Committee and a former member of the AIAA Intelligent Systems Technical Committee.

In her presentation, she explained the difference between control and feedback control. “Control is the use of algorithms and feedback in engineered systems to alter system behavior, while feedback control is the basic mechanism by which systems maintain their equilibrium,” she said.

To view the entire lecture, join the GoFly Prize challenge by contacting info@goflyprize.com.

There must be something in the water at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. Home to the team that won the original SpaceX Hyperloop competition in January 2017 with the best overall pod, the university has produced another team of innovators ready to shake up the aviation space. Team Silverwing, one of five winners of Phase II of the GoFly Prize, has built an electric flying motorcycle designed for autonomous flight at speeds topping 60 mph.

Not surprisingly, Delft’s engineering and aerospace departments have become world famous, with faculty and staff involved in a number of high-profile projects. So when Silverwing Team manager James Murdza and technical manager Victor Sonneveld learned about the GoFly Prize and set out to build their device, the S1, the two had plenty of talent to recruit, including a few Hyperloop veterans.

Silverwing is one of the bigger teams to win Phase II of the GoFly Prize. It’s currently made up of about 30 members and counting, including students and professors from 10 different countries with expertise in eight different disciplines across six of the university’s engineering faculties. Despite its size, Silverwing is a tightly-knit family, Murdza says—a family unified in its aim to get their S1 prototype scaled up, fine-tuned and ready for GoFly’s Final Fly-Off in 2020.

Making Mentorship Count

Mentorship has played a critical role for Silverwing, as the team makes a continued effort to consult with university advisors, manufacturers, and GoFly Masters—including Dr. James Wang, senior vice president of Leonardo Helicopters and the former vice president of research and development at AugustaWestland. Known as the “Steve Jobs of Rotorcraft” by those in the industry, Wang has shared his expertise in helicopter design and advised Silverwing on how to design test flights and use different-scaled models to build up to a full-size version.

Meanwhile, when it came time to optimize the propellers for the S1, Silverwing turned directly to their manufacturer for insight. “We knew the company that made them would have the best insight into what would work, so they helped us find the right dimensions of the blades for our device. We’ve been working with manufacturers a lot in this respect, so you could say that they’ve become our advisors as well,” Murdza explains.

Internally, the team is brimming with subject matter experts too, including electrical engineers, industrial designers and aerospace professionals who were instrumental in building Delft’s Hyperloop pod. “There’s a tremendous amount of cross-collaboration and mentorship that takes place within the team, especially because we represent various education levels,” says Murdza.

This diversity of expertise has played a critical role in advancing Silverwing’s design. The suggested introduction of an aerodynamic shell around the pilot, for example, has tremendously reduced drag on the device and improved its performance. Even the orientation of the device has evolved. In its current iteration, the S1 is powered by two ducted fans that enable the device to sit on its tail for take-off and landing but rotate into a more horizontal position for flight. “There’s a lot of little detail tweaks we’ve made as well,” Murdza adds. “Small changes have made a big impact.”

Scaling and Soaring

For Silverwing, Phase II of the GoFly prize was all about testing and analysis. Because one of the Phase II requirements was to log actual flight time, the team was determined to get its half-scale model up in the air as much as possible. Yet even this large team struggled with the amount of time and volume of resources needed to execute successful test flights.

“When you test something for the first time, things break and then not only do you need time to fix them, but you also need new parts. It’s a complicated process,” Sonneveld explains. Still, Silverwing found ways to overcome challenges, tackling one hurdle at a time. “When the batteries we were using were presenting problems, we switched to a cable that made it easier to test flight. It’s all about isolating the problem and solving for it.”

The team also considers itself lucky because so far, things have managed to “work out,” just in the nick of time. But what Sonneveld attributes to luck is more likely the work of tireless perseverance. One “lucky” moment came just before the Phase II deadline when the team was executing a critical test of their new electric motor. Silvering knew they were cutting it close with testing, but logging the flight hours was vital, so they spent 12 hours in a freezing cold F-16 aircraft shelter testing the device—and it was a success. “It was a really tough day but the result was so satisfying. It made it all worth it,” Sonneveld says.

As Silverwing looks ahead to Phase III and the Final Fly-Off, Murdza, Sonneveld and rest of the team are eager to bring their full-size device to life. “It’s one thing to run prototype tests and simulations but to fly the real thing—we can’t wait for that moment,” Murdza says. And once the S1 is realized, the electronic helicopter’s applications will be vast, ranging from disaster response and offshore rescue operations to recreational use. “It will exceed the capabilities of any existing device,” says Murdza. “To fully understand its potential, you have to let your imagination run wild.”

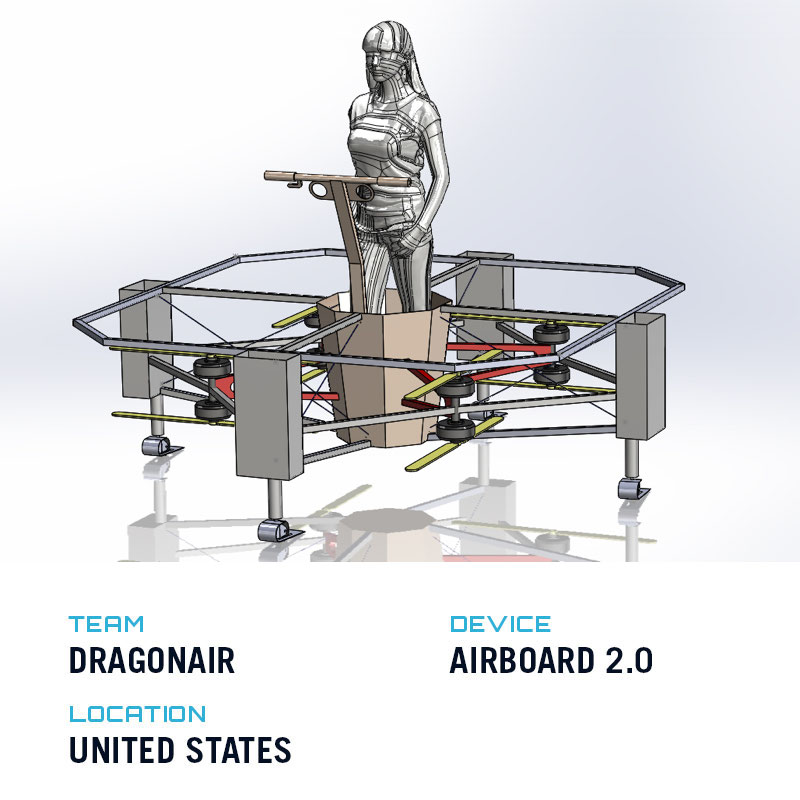

Team Dragonair’s project manager Mariah Cain gained first-hand experience in turning creative sparks into tangible projects at a young age, growing up in her grandfather’s machine shop. Eventually, she moved out of her small town and began working at a 3D imaging company in Arizona. There, she became interested in Hydroflight, a competitive sport in which athletes maneuver on water-powered hoverboards connected to jet-skis. It was through their mutual interest in Hydroflight that Cain met her now-teammate Jeff Elkins, who was working to marry the technology behind Hydroflight devices and drones to develop a new class of personal flyers.

Far more than just an enthusiast, Elkins, who has been called a “mad scientist” by his peers, is a drone pilot with extensive engineering experience, having designed everything from prosthetic limbs to architectural renderings. His expertise, along with Cain’s own growing interest in Hydroflight and personal aviation, drove Cain to move down to Florida and get serious about what she once considered just a hobby. There, she started working closely with Elkins and his colleague Ray Brandes on Elkins’ most ambitious project to date—the Airboard, a flying device that gets its power from eight motors and its maneuverability from the human body.

Over time, a true team took shape, complete with a clear vision, engineering prowess and perseverance. But making a flying device is a monumental challenge, not to mention the work that goes into securing funding, gaining industry recognition, and attracting public interest. As project manager, Cain knew she had to find ways to make these critical elements come together—that’s when she heard about the GoFly Prize.

A Team of Pilots and Engineers

Though the GoFly Prize challenge was issued in September 2017, Cain and her colleagues only learned about the opportunity in April 2018. Having missed the Phase I submissions deadline, Cain, Elkins, and Brandes joined the competition during Phase II, incorporating as team Dragonair and completing their entry just in the nick of time.

Their device—now called the Airboard 2.0—has undergone many iterations even before Dragonair joined GoFly, but the team had to make a number of new key changes to be considered for Phase II. They needed to make their prototype smaller, boost flight time without overloading the device with heavy batteries, and obtain new test parts for their improved model.

Through it all, Cain has played a major role in experimentation, flying the Airboard using her body movements to control it—just take a look at her impressive flight on YouTube. “Many people ask me if it’s scary to fly, but because of all the safety stabilization, it feels natural. It’s exciting to be one of the first women involved in this style of flight. I’m grateful that I get to be a part of such a unique field at such an incredible time in history,” Cain says.

Creating the feeling of freely flying through the air, uninhibited by a massive device, was a big factor in Dragonair’s design process. “The Airboard enables you to interact with the natural world around you. It’s very empowering compared to other technologies that take away from the human connection with nature. The Airboard’s design allows the pilot to feel like they are one with the device, informing its motion by shifting their weight it in a standing position. Once people get a taste of what it’s like to fly these things, they won’t be able to get enough,” Cain says.

Don’t let the team’s focus on pure human flight fool you, though—for Dragonair, safety is a major priority. Already, the device has a mechanism in place where it can continue to fly even if up to four of its eight motors give out. In total, there are three tiers of safety conditions in place to ensure that flights are safe. For example, there will be two separate parachute systems installed (one for the pilot and one for the device).

Making the Inevitable Real

As futuristic as the Airboard may seem, it’s becoming real faster than Dragonair had imagined. Cain and Elkins say that the progression from unmanned drone to personal flyer is inevitable, especially once people can envision all the possible applications of these devices. So how does team Dragonair expect the Airboard to be used? Recreation, of course, will be a big draw. But Cain has loftier ambitions as well: “We need to get more girls on these devices to show the world what women can do,” she says.

She also believes that there’s a great deal of potential when it comes to search and rescue operations.“I recently lost a good friend to a riptide,” she says. “When something like that happens, all these boats and helicopters are dispatched but it’s so hard to find someone when you’re on such an unwieldy vehicle. A smaller device with a spectral camera can make it easier to find people and save lives.”

Personal flyers can even drive change in the agricultural space, where the eradication of harmful plants is currently not done in the most environmentally sound way. Today, aircraft with limited targeting capabilities spray harsh chemicals on massive areas of wildlife, killing not only certain flora but also their surrounding ecosystems. A heavy-lifting drone—manned or unmanned—can execute that task more sustainably simply because it can get lower to the ground and aim more precisely.

“There’s really no limit to how these devices can add efficiency to different industries,” Cain says. “We can’t wait to finally complete the Airboard that we’ve dreamt about for so long and show the world its capabilities.”

Vladimir Spinko isn’t the first to dream of a world where the speeder from the famous forest chase scene in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi truly exists—but he is among the first to actually build something resembling it. One of five winners of Phase II of the GoFly Prize, Spinko and his nine fellow members of team Aeroxo have successfully built a working prototype of the ERA Aviabike (which Spinko describes as “a flying motorbike”) and are working towards making a full-size device ready for the GoFly Prize Final Fly-Off, set for early 2020.

Back in 2007, the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology graduate was working at investment firm I2BF Global Ventures as an analyst, handling deal sourcing, assessing technology and performing due diligence. But he wanted to do more than help fund new technology. He wanted to create it.

So, armed with colleague Eldar Razroev’s idea for the first-ever small commercial tiltrotor UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) and an early investment from I2BF’s Ilya Golubovich, Spinko and his tight-knit team co-founded Aeroxo in September 2014.

Drone Meets Driver

Spinko and Aeroxo’s other founding members Golubovich and Razroev got to work immediately, assembling a team of seasoned experts, eager second-year students and other contributors from across Moscow and Kazan who were capable of actualizing the tiltrotor UAV Spinko envisioned. But for about two years, the team struggled to get the device off the ground—literally. It wasn’t until the fall of 2016 that Aeroxo’s Moscow-based engineers executed their first successful test flight, lifting into the air a drone that looked very different from the team’s original design.

“That’s when we learned an important lesson: an ugly drone that can make transitions and fly is much better than a beautiful model that can’t take off,” Spinko says.

By 2017, the team was ready for the public to see their creation. Although they were hesitant to take their drone out of the safety of their lab where equipment and spare parts were at their fingertips, Aeroxo brought it to an exhibition in Austria, where the tiltrotor UAV withstood the test of a 2000km flight. The team knew then that they could take the device to the next level.

“Our first step was to participate in a challenge to create a large passenger drone or aero taxi,” Spinko explains. “Our design made it to the finals, but failed to win. Still, at this point, we had never built anything larger than a 35kg drone. This was our first attempt to build something that could carry a passenger, so this was a big step forward for us.”.

Eventually, the team found itself building a flying passenger vehicle that took on many different forms—a drone taxi capable of carrying several people, a small SUV with motors and rotors capable of driving and flying, and several other designs. But this wasn’t the team’s forté, and Spinko knew it.

“We had never set out to build a flying car,” Spinko recalls. “We had our tiltrotor and that’s where we needed to direct our focus. And then we finally had our breakthrough realization: why can’t a pilot just ride a large tiltrotor?” The team’s aerodynamics expert put together an early sketch of a rideable tiltrotor resembling a motorbike, and the rest is history—or perhaps, the future.

Reaching Industry Recognition

Eager to get their design in front of industry experts from Boeing, Pratt & Whitney and others, Aeroxo prepared to enter the ERA Aviabike into the GoFly Prize, but knew they had to get input from expert users first. The team solicited the input of professional bikers, welcoming their feedback on everything from the driver’s seat design, to the maximum speed and potential cost.

Within days, Aeroxo completely rearranged how a pilot would ride the Aviabike, modified the accessories to make the device more affordable overall, and made other changes based on the suggestions of its target demographic. It was only after that that the team entered GoFly’s Phase I and won, along with nine other promising teams. “The feedback we’ve received from our GoFly mentors has been invaluable,” Spinko says. “For example, they’ve encouraged us to rethink the diameter of our propellers, and we’ve been able to achieve 10 to 12 percent better performance as a result.”

Now a Phase II winner with a working prototype, Aeroxo continues to make improvements and inch closer to a full-size device, but the journey only gets more challenging. Though their signature tiltrotor has gotten them this far, Spinko says that the team is coming to terms with the fact that for a full-size model, the tiltrotor will have to be redesigned. “We’ve gotten some data back from field tests, and we now know that we need to make a number of modifications, including altering and finetuning our wingspan and number of wings, in addition to redesigning the tiltrotor mechanism,” Spinko explains.

GoFly’s size requirement, which states that the maximum single dimension in any direction between two planes cannot exceed 8.5 feet, not including the operator, has been Aeroxo’s greatest challenge thus far, and Spinko anticipates that it will remain the toughest criteria for the team. “We’ve been pleasantly surprised in some ways. Our prototype is virtually silent, for example. It’s 10 to 15 percent quieter than we predicted. But the size — that’s going to be a hurdle,” he says.

Nevertheless, the team is determined to debut the full-scale ERA Aviabike at the GoFly Final Fly-Off. And from there, the possibilities are vast. Whether the device is primarily adopted by the biker community as a recreational vehicle, or becomes a search and rescue staple that helps first responders save stranded climbers in the corners of the Swiss Alps not accessible by helicopter, Aeroxo knows ERA Aviabike will transform transportation. It’s only a matter of time.

Our corporate sponsor Pratt & Whitney believes that powered flight has transformed—and will continue to transform—the world. It’s an engine for human progress and an instrument to rise above. That’s why the company works with an explorer’s heart and a perfectionist’s grit to design, build, and service the world’s most advanced and unrelenting aircraft engines.

Over the summer, at the Farnborough International Airshow in Farnborough, England, Pratt & Whitney unveiled their commitment to joining the GoFly community, announcing their sponsorship of the Disruptor Award, which will be presented to one team that is truly innovative, going beyond in developing their personal flying device for the competition.

For Pratt & Whitney, the partnership with the GoFly Prize Challenge felt like a natural fit. “Both organizations believe in innovation, and pushing the boundaries of the future of flight,” Colleen Lynch, communications manager, employer of choice and recruitment, at Pratt & Whitney, said in an interview. What’s more, Lynch said that beyond eagerly watching GoFly Teams try their hand at building personal flyers, Pratt & Whitney hopes that GoFly will bring excitement to the industry and inspire a new generation to show interest in aviation careers.

Below, Lynch shares Pratt & Whitney’s perspective on the competition and offers some advice to participants.

GoFly: What’s it like to work at Pratt & Whitney? What do you find most rewarding about the organization?

Colleen Lynch: The thing about Pratt & Whitney is there are so many opportunities to not only learn about the various fields within the aviation industry but also to grow your career around the world. You could start in our East Hartford, Connecticut headquarters. Then, in a few years, you might want to take advantage of an opportunity and go work in our Singapore location.

Our employees have a wonderful opportunity to utilize our Employee Scholar Program, and continue their education in areas that interest them. Whether it’s getting your master’s or finishing your bachelor’s, there’s a lot of room for growth because the Employee Scholar Program pays for tuition, academic fees, and books at approved educational institutions.

GoFly: Why is it important for Pratt and Whitney to support the GoFly Prize? How does it align with some of your initiatives?

Lynch: The GoFly Prize is in great alignment with Pratt & Whitney because both organizations believe in innovation and pushing the boundaries of the future of flight. We’re really excited to see what teams will be coming up with and developing.

GoFly: What are some of your hopes for the winners of Phase II, and beyond that? What kinds of personal fliers would you want to see take flight?

Lynch: What’s unique about Pratt & Whitney is that our employees have this natural curiosity around aviation and the future of the industry. Seeing what others that have that same curiosity are coming up with and designing is exciting. We can’t wait to see all the different innovations and iterations of personal flight. It’s an opportunity for us to learn as well.

GoFly: What are some of your expectations for the winner of the Disruptor Prize?

Lynch: We’re looking at the Disruptor Prize with our eyes wide open. We are not putting in any major parameters. We want to see what these teams develop, and how they are disrupting the industry because it might be a learning opportunity for us. A broad mindset allows us to look for that next big thing. These teams have already demonstrated a huge amount of innovation and curiosity, so the Disruptor Prize is going to be a really fun award for us to review. It gives us the opportunity to reward that team that has gone beyond to come up with something really cool.

GoFly: What do you think some of the biggest challenges for competitors will be as we continue further into the competition?

Lynch: Teams are getting to the stage where they have to prove their concepts, so that’s going to probably present some opportunities and challenges. As they keep reiterating their designs, there will be difficulties. But, these teams have risen to the occasion time and time again, so we know they can do it.

GoFly: With Phase III underway, what advice do you have for GoFly Prize competitors?

Lynch: Just keep going. There’s going to be frustration along the way. It might seem impossible, but you’ve made it this far, so keep going. And remember: At Pratt & Whitney, we have mentors available on our legal team, our social media team, and, of course, two of our really great engineers are available as well. So, use the mentors not only from Pratt & Whitney, but also from other sponsors of the competition. Use their expertise and their experiences to help you as you move forward.

GoFly: If you could say one thing to the entire innovator community, not just Phase III teams, what would it be?

Lynch: Here at Pratt & Whitney, we’re calling the curious. Advancing the future of flight is what we do every day around the world with over 41,000 employees. If you have what it takes, we want to hear from you.

GoFly: If you had your own personal flying device, where would you fly and why?

Lynch: I just went to London for the first time and that was really great. My daughter would probably want me to choose Barcelona. Actually, a friend of mine and her daughter recently traveled to Morocco, and that would be really interesting to see. If I had a jetpack and could zoom off there, how great would that be?

Congratulations to all of our innovators and teams for completing Phase II of the GoFly challenge! We were incredibly impressed with the technical prowess and creativity of the entries—in fact, we received so many stellar high quality entries that we have added an extra prize, and will now be awarding 5 Phase II Teams with prizes. Each of these teams will receive $50,000 in prizes.

The GoFly community is comprised of more than 3,500 innovators from 101 countries across the globe. Of these innovators, 31 Phase II Teams across 16 countries submitted entries for review by a panel of experts across 2 rounds of rigorous judging. These Phase II teams were required to submit visual and written documentation detailing their personal flyer prototypes. It’s the first time physical prototypes were introduced into the challenge, and this crucial step has brought us ever closer to the Final Fly-Off.

Join us in congratulating our winning teams on their achievements and in thanking our partners and sponsors for their support of the GoFly Prize and our innovators. Major partners include Grand Sponsor Boeing, Corporate Sponsor Pratt & Whitney, and over twenty other major aviation and innovation organizations that offer resources to our competitors and participate in our Masters and Mentors program.

And now, without further ado, meet our Phase II winners (in alphabetical order):

Latvia and Russia

The ERA Aviabike is a tilt-rotor aerial vehicle type that combines the VTOL capabilities of a helicopter with the range and speed of fixed-wing aircraft. ERA Aviabike is a flying bike.

United States

The Airboard 2.0 is a multicopter for human flight.

Netherlands

The SI is a canard-wing configuration around a person in motorcycle-like orientation powered by two electric motors with ducted rotors. The aircraft makes a 90-degree transition from vertical take-off to horizontal cruise flight.

United States

The Aria is a high-TRL compact rotorcraft designed to minimize noise and maximize efficiency, safety, reliability, and flight experience.

United States

The FlyKart2 is an electric, single-seat, multi-rotor, ducted-fan, VTOL aircraft designed to be inexpensive to build, own, and operate.

Editor’s Note: We’re excited to introduce you to the innovative, bold, and talented individuals competing in GoFly. Our teams come from all over the world, shaped by their diverse backgrounds and unique life experiences. We can’t wait to see what they’ll build, but in the meantime, get to know the people behind the devices.

For Rob Hart, member of Team Aviaereo in Cambridge, UK, the beauty of aviation lies in aircraft design. Though in the early days of his career he had the opportunity to try his hand at different areas of aviation and aircraft production, it was on the design floor, surrounded by drawing boards, where he found his calling.

Today, Hart and his team are working on the Aereo-bee, their entry for the GoFly Prize, in the hopes that personal flyers will one day fill the skies. Read on to get to know more about Hart’s childhood and family, which have shaped his interests and career.

What are your earliest memories associated with aviation?

My earliest memories of flight are building model gliders with my dad when I was a child. Both my older brothers built planes too and we flew them at Cobham Common Flying Club on weekends. My first glider was a cable launch and I remember running through the field, holding the cable and pulling it up into the air.

When did you decide to pursue a career in aviation?

When I took my first job as an engineer’s apprentice, I had already decided that I wanted a career as a designer. They started me out in the sheet metal shop and then from there I worked my way around all the manufacturing facilities, working on composites and electrical as well as in the machine shop and tool room, on the assembly line, and in the test center. When I finally arrived in the design office, I knew that was where I wanted to be.

We were designing aircraft interiors and in those days it was all done by hand. There were a couple of computers and some CAD workstations, but all of the conceptual work and ideas were created on the drawing boards. That’s when I felt like I had a career as an aerospace engineer—at my drawing board.

Was there someone who inspired your interest in aviation when you were a child? Who did you look up to?

Growing up, my older brothers both built model planes of all kinds: control line, radio-controlled, gliders, helicopters. When my Dad helped me build and fly my first glider, I think perhaps that moment when it first launched up into the air was when I was inspired by him.

What were some of your favorite courses in school? How did they enrich your understanding of aviation?

I studied at Farnborough, which has strong ties with the aerospace industry. There were often chances to learn about aviation history and the developments that were made way back and are still just as relevant today.

What excites you about GoFly?

The GoFly competition is making it possible for me to build and test-fly my device, the Aereo-bee. That’s what I’m most excited about—building it and seeing the idea become real.

What is your biggest challenge in the GoFly Prize competition currently? How do you plan to overcome it?

I have a full-time job and the biggest constraint on me so far has been time. I would really like to expand the team and take on more members. It would be great if someone could do some work on the device graphic, for example. I was really impressed by the graphics submitted in phase I and my team is desperate for someone to improve our graphic.

Our safety assessment also requires a lot of effort, because we need to prepare for the flight readiness review. The document is currently just a shell and we need to rally around it as a team or introduce an additional team member to coordinate our safety reviews, keep the hazard log up to date, and conduct risk assessments and zonal hazard analysis.

What does the world look like after you create your flying device? How do you think you will change the world?

I imagine the sky will be full of Aereo-bees buzzing around above.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received from a mentor?

Measure twice, but cut once. The problem is my mentor never told me which one of the two measurements I should use.

Editor’s Note: Over the next year, we will be hosting a series of GoFly Master Lectures where industry experts share advice, insights, and answer questions from GoFly Teams.

For the latest in our series of “Master Lectures,” we welcomed Gregory Bowles, vice president of Global Innovation & Policy for the General Aviation Manufacturers Association. Bowles is responsible for the identification of key technological opportunities to evolve the global safety, efficiency and success of aviation. Greg leads the GAMA Electric Propulsion & Innovation Committee (EPIC) which represents the world’s leading aviation mobility development companies along with traditional aviation manufacturers as this community strives to enable new kinds of public transportation through the air. Greg also currently leads the worldwide design standards committee which is chartered to develop globally acceptable means of compliance for general aviation aircraft.

Prior to joining GAMA, Bowles worked as a certification engineer at Keystone (now Sikorsky) Helicopter, and was a design engineer at Cessna Aircraft Company (now Textron Aviation). Bowles holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Aerospace Engineering from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and a Master of Business Administration degree from Webster University. He is an active instrument rated general aviation pilot.

“The reason I pivoted fully to hybrid and electric technology is because I believe this is a disruptive change to the aviation industry,” he said in his Master Lecture.

To view the entire lecture, join the GoFly Prize challenge by contacting info@goflyprize.com.

Editor’s Note: We’re excited to introduce you to the innovative, bold, and talented individuals competing in GoFly. Our teams come from all over the world, shaped by their diverse backgrounds and unique life experiences. We can’t wait to see what they’ll build, but in the meantime, get to know the people behind the devices.

Whether they’re taking a course in an entirely unfamiliar subject area to expand their knowledge base, or working with new mentors to help guide their device development, our GoFly Prize participants are innovative, bold and resourceful. Farid Saemi from Texas A&M University’s Team Harmony Aeronautics, for example, once signed up to work on a mechatronic project without any prior knowledge of soldering—and succeeded.

Saemi has brought this can-do attitude to his team’s GoFly Prize entry as well, as they continue to build and improve upon their personal flying device together. Read on to learn more about Saemi’s hidden interest (hint: it involves Frank Sinatra!) and his vision for the future of flight.

When did you decide to pursue a career in aviation?

If you look at my fifth-grade yearbook, my dream job was: “Aeronautical aerospace astronautical engineer,” so I’ve known I wanted to pursue a career in aviation for quite some time.

Was there someone who inspired your interest in aviation when you were a child? Who did you look up to?

I’ve always been interested in history, so I’m inspired by the rich multilateral history of aviation. The Wright Brothers pioneered flight, but a lot of German scientists developed the technological foundations of modern aviation in the 30s and early 40s. In the 60s and 70s, Boeing and the “Scots” (McDonnell-Douglas) then brought aviation to the masses, and now teams from around the world are working to bring personal flight to the masses.

What were some of your favorite courses in school? How did they enrich your understanding of aviation?

My junior and senior level courses were definitely the most interesting. “Helicopter dynamics” taught me the fundamentals of vertical flight, and “Aerostructure optimization” showed me how every system of an aerospace system is so tightly coupled.

What excites you about GoFly?

I’m most excited about the opportunity to develop the next generation of aviation as a fresh engineering graduate. I would not have been able to learn so many different hands-on technical and business skills had I gone straight to industry as a standard aerospace engineer.

What is your biggest challenge in the GoFly Prize competition currently? How do you plan to overcome it?

Fundraising has been the biggest challenge to our team of all-technical people. However, we’ve received a lot of fiscal and targeted educational support from Texas A&M University and the broader Aggie Alumni Network.

What does the world look like after you create your flying device? How do you think you will change the world?

A personal flying device will likely have very practical military and civilian applications, such as distributed air search and rescue. However, I’m most interested in the pure joy aspect of personal flight. Can you imagine flying through someplace like the Grand Canyon in Arizona or the Simien Mountains in Ethiopia?

What’s one fun fact about you that your team members don’t know? What is something we should know about you?

I’m an Old Soul music listener: Sinatra, Dino, and Darin are some of my favorite singers. I can’t wait until we develop a two-person version of our vehicle and I can take a date out for a spin to the tune of “Come Fly with Me.”

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve ever received from a mentor?

Go beyond your comfort zone. My freshman year, I volunteered to repair a mechatronic project even though I had no experience soldering or mechanically fabricating things. I failed to meet the original deadline, but I sought help and got a second chance to repair the system. That project led to controls and avionics research as a junior (and a controls internship at Boeing), and that work led to electrical powertrain research in grad school, which brought me to now serving as the electric propulsion lead for our team.

Want to see your team featured in a Q&A as well? Fill out our questionnaire to get started!

Editor’s Note: Over the next year, we will be hosting a series of GoFly Master Lectures where industry experts share advice, insights, and answer questions from GoFly Teams.

For the latest in our series of “Master Lectures,” we welcomed Johnny Doo, president of International Vehicle Research Inc, for his presentation titled “eVTOL for Public Services – Design & Applications.”

Doo focuses on innovative manned and unmanned flight vehicle technology and product development while supporting global rescue and disaster relief initiatives. He also leads the NASA coordinated Transformative Vertical Flight – Public Services working group, teaming with 50 industry and institution experts as well as executive members to develop the roadmap for search and rescue, disaster relief, police and firefighting, medical transport and military eVTOL applications. He has over 30 years of experience in managing and developing aviation products from high performance piston aircraft, personal and business jets to unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV).

He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Mechanical Engineering and a Master’s degree in Aerospace Engineering. He is also the co-author of the book WIG Craft and Ekranoplan – Ground Effect Craft Technology.

His biggest advice for GoFly competitors? “Right now, everyone has a different idea for what will work best. There are many different ways to address the challenges and opportunities of VTOL design,” he said.

To view the entire lecture, join the GoFly Prize challenge by contacting info@goflyprize.com.