The dream of flying on demand, perhaps just mere steps from one’s front door, is edging closer to reality. One organization interested in this pursuit is the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), a GoFly Prize partner. In the following Q&A, Ben Iannotta, editor in chief of Aerospace America, the magazine of the AIAA, and staff reporter Tom Risen discuss how the era of personal flying devices could soon be upon us if engineering challenges are overcome and society embraces the new-fangled means of getting from here to there.

The following is an edited transcript of the discussion. The participants have been provided the opportunity to amend or edit their remarks.

Q: What are the best arguments for why an era of personal flying devices might actually—finally—be upon us?

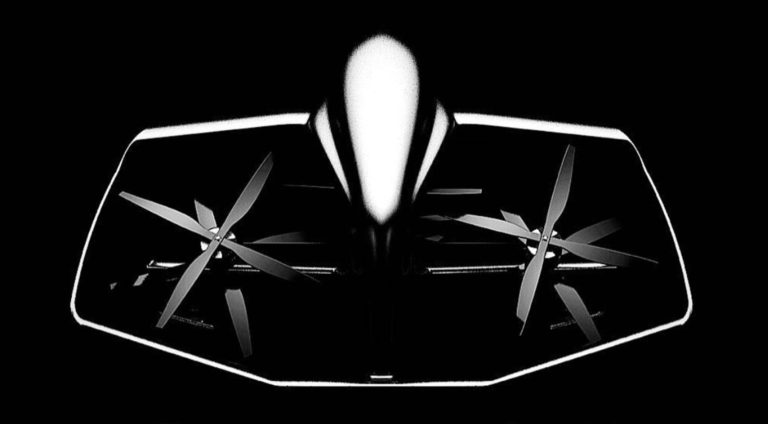

Tom: People building personal flying devices are very excited about electric propulsion. It makes a whole bunch of designs possible that aren’t with traditional mechanical and chemical-powered propulsion.

Ben: That’s right. In terms of technology, some of the groundwork, if you will, for electric propulsion has been laid by the drone industry. Electric propulsion will be quieter, which it’ll have to be to go into neighborhoods in the morning.

Tom: A second main “why now?” argument for personal flying devices is the success of ride-sharing apps. A repeated sales pitch I hear from companies that want to build so-called flying taxis is that people will pay extra money to go where they’re going faster by air, because time is the only thing you can’t get back in this life.

Q: Tom, you wrote a story for Aerospace America last year about this growing interest in sky taxis. Uber is creating partnerships to help companies develop such automated, drone-like, propeller craft for passenger transportation. Will personal flying devices initially be designed to likely appeal to commuters more than recreators?

Tom: My reporting indicates that commuters will be the first big market because of high rideshare demand.

Ben: Based on the history of technology advances, though, it can be pretty darn hard to predict how human beings will end up using something. There’s so many applications for drones these days that I don’t think people anticipated initially.

Q: What do you see as the biggest technological and engineering hurdles that still must be overcome for personal flying devices?

Tom: Many engineers I’ve spoken with point to batteries. Batteries have not kept up with our technological prowess. Battery endurance and safety are going to be very important. Some engineers have suggested that at first, flying taxi companies might have to swap out batteries every flight, just to make sure they’ll have the energy needed to fly 30 minutes.

Another big issue is autonomy. Many people pursuing personal flying devices want them to operate on their own, without human “pilots,” which will cut down on human error, boost safety, and potentially slash costs. It’s one of the same arguments for driverless cars.

Ben: Tom’s reporting shows how critical autonomy is to growing this market in the long-term and getting a high volume of flights. I would not want to see everybody on my morning commute on the Fairfax County Parkway suddenly go airborne at the controls! I’d feel better about autonomy in crowded air spaces.

Tom: Air traffic management will be a challenge. Most of the designs for personal flying devices—or sky taxis, jetpacks, whatever they might be—are smaller than planes or helicopters, and for a business to profitably operate them, they would need to have a lot of customers. That means there’ll be many, many small aircraft adding to the traffic that’s in the sky already.

Q: Could social acceptance be an even bigger hurdle to personal flying devices? Some people remain afraid of flying on airplanes, a technology that’s over a century old.

Tom: We’ll see problems with social acceptance the way we have with other flying devices in history. YouGov did a survey last year showing that more than half of the consumers surveyed said they’d feel unsafe riding in a driverless drone. And about four out of five respondents said that they’d have to have the option of taking control of the drone to even consider riding in one.

Ben: When I think about social acceptance, I’ve always suspected that humans evolved to be terrified of falling. That explains why flying can be both frightening and thrilling. If you look at the history of flight, if past is prologue, we could overcome this fear. As the airline industry constantly reminds people, air travel has actually long been safer than driving in your car.

Q: Would you see yourself as a potential early adopter of personal flying devices?

Tom: I was always interested in the supersonic Concorde when I was younger. I didn’t think about jetpacks as much, but I did like flying in a helicopter this one time with my friend. So I’d probably be interested in a personal flying device that resembled a rotorcraft.

Ben: Trust me, as far as operating vehicles, we’re all glad that I stick to cars and boats and things that operate in two dimensions. [Laughter] That said, I do love flying and aircraft and spacecraft, no doubt. I just think it’s amazing that humans have been able to open up this vast territory above us.